In April, I appealed a decision by the W3C Chairs to place DID Methods in scope in the next DID WG Charter.

That appeal was ignored and the charter advanced to AC Review.

This is our Formal Objection to that charter.

We oppose this charter on several grounds.

- Process

- Collaboration

- Technical Fundamentals

- Interoperability Goals

PROCESS

We stand by our appeal (https://blog.joeandrieu.com/2023/04/12/fighting-for-consensus-at-the-w3c/), which we feel was improperly handled. The Process rules, about consensus, appeals, and Formal Objections, in our opinion, were ignored.

The incident (and the appeal) were filed under Process 2021; the current process is Process 2023. Staff’s response meets the requirements of neither Process. Since Philippe Le Hegaret cited Process 2023 in his response to my appeal, let’s look at what Process 2023 requires.

Process 2023 requires Groups to formally address issues with a response that includes a rationale for decisions that “a W3C reviewer would generally consider to be technically sound”. Neither Philippe Le Hegaret’s nor the Chairs’ responses met that standard. Philippe simply claimed that “this charter is the most acceptable for the majority of the group (an assessment that was confirmed by a recent poll); and that 2) the charter is not a WG deliverable, and consensus must be reached at the AC level anyway, so Joe’s argument should be raised during AC review, not prior to it.”

Unfortunately, the cited poll did not even attempt to gauge consensus. It merely gauged the popularity of advancing the WG, without consideration of the multiple options under consideration by members of the group. Rather than attempting to establish a legitimate vote, Staff created a poll that, like a Politburo election, only offered one candidate to vote on, where, in fact, it should have been inquiring about any objections to best understand the proposal with the weakest objections, instead of blatantly attempting to rubber stamp the offending decision.

More problematic is that the rules for Formal Objections were not followed. There should have been a W3C Council formed to evaluate the objection on its own merits, prior to AC Review.

Staff’s assertion that “consensus must be reached at the AC level anyway” is fundamentally in error. The AC is not involved in resolving formal objections. Councils are.

According to Process 2023, a Council MUST be formed to consider the merits of the objection.

Given that the objection was filed April 12, Staff should have started a council no later than July 11, 2023. PRIOR to sending the Charter to review by the AC. Unfortunately, no council was formed. Instead, on July 26, Philippe finally responded to the appeal by saying Staff is going to ignore it. On August 8, the charter was proposed, unchanged, to the AC for review.

One may raise the concern that the new process was not adopted until June 12, leaving Staff only a month before the deadline. However, Staff did not have to wait until the process was adopted. They could have responded under the previous process any time before June 12 or, realizing that the process was likely to be adopted, they could have begun the prep work to start the council in a timely manner, as required. The idea of councils had been extensively debated and iterated on months before I filed my appeal to the chair decision. And yet, we still have no council.

Further as part of its obligations under Process 2023 when there are Formal Objections, Staff is tasked with investigation and mediation. Since Staff’s efforts in that regard did not lead to consensus–by Staff’s own acknowledgement–its only option is to form a council and prepare a report:

“Upon concluding that consensus cannot be found, and no later than 90 days after the Formal Objection being registered, the Team must initiate formation of a W3C Council, which should be convened within 45 days of being initiated. Concurrently, it must prepare a report for the Council documenting its findings and attempts to find consensus.”

As a result, the AC is reviewing not the legitimate continuation of the DID Working Group, but rather a hijacking of the work that I and others have given years of time and effort to advance.

COLLABORATION

Taking the charitable position that everyone involved continues to act in good faith and the process as defined was properly followed (even if its documentation might be inadequate), then we still oppose this charter on the grounds that the development of the charter violated the fundamental purpose of the W3C: collaboration through consensus.

The question we ask is this: should WG chairs be able to propose a continuation of that WG without consensus from the WG itself? Should anyone?

This is the situation we’re in and I did not expect that collaboration at the W3C would look like this.

I first got involved with W3C work by volunteering feedback to the Verifiable Credentials Task Force on their draft use case document. From those early days, I was asked to join as an invited expert and have since led the use case and requirements efforts for both Verifiable Credentials and Decentralized Identifiers, where I remain an editor. I also developed and continue to edit the DID Method Rubric a W3C NOTE. Somewhere in that tenure I also served as co-chair of the W3C Credentials Community Group.

During this time, I have been impressed by the organizations’ advocacy for consensus as something unique to its operations. The idea of consensus as a foundational goal spoke not only to my heart as a human being seeking productive collaborations with others, but also to my aspirations as a professional working on decentralized identity.

And then, citing a non-binding recommendation by the then-acting director in response to previous Formal Objections, the chairs of the DID WG turned that narrative of consensus upside down.

Here’s what happened:

June 30, 2022 – DID Core decision by Director “In its next chartered period the Working Group should address and deliver proposed standard DID method(s) and demonstrate interoperable implementations. The community and Member review of such proposed methods is the natural place to evaluate the questions raised by the objectors and other Member reviewers regarding decentralization, fitness for purpose, and sustainable resource utilization.” Ralph Swick, for Tim Berners-Lee

https://www.w3.org/2022/06/DIDRecommendationDecision.html

July 19, 2022 – DID WG Charter extended, in part “to discuss during TPAC the rechartering of the group in maintenance mode.” Xueyuan xueyuan@w3.org https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-did-wg/2022Jul/0023.html

August 18, 2022 – Brent Zundel proposed to add DID Methods in PR#20 https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/20

September 1, 2022 – Group email from Brent Zundel about TPAC “We plan to discuss the next WG charter and will hopefully end up with a draft ready to pass on to the next stage in the process.” Brent Zundel https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-did-wg/2022Sep/0001.html

The Charter at the time of announcement https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/blob/af23f20256f4107cdaa4f2e601a7dbd38f4a20b8/index.html

September 12, 2022 – Group meeting at TPAC “There seems to be strong consensus that we’d rather focus on resolution” https://www.w3.org/2019/did-wg/Meetings/Minutes/2022-09-12-did

September 20, 2022 – Summary of TPAC. Manu Sporny msporny@digitalbazaar.com “The DID Working Group meeting had significant attendance (40-50 people). The goal was to settle on the next Working Group Charter. […] There were objections to standardizing DID Methods. […] There didn’t seem to be objections to DID Resolution or maintaining DID Core.”

https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-credentials/2022Sep/0177.html

September 21, 2022 – PR#20 from Brent Zundel merges, without discussion or any notice to the WG, PR#20 DID Method resolution into spec, saying “I am merging this PR over their objections because having the flexibility to go this route could be vital should our efforts to move DID Resolution forward be frustrated.”

October 18, 2002 – DID Resolution PR #25 created to add DID Resolution

October 24, 2002 – DID Resolution PR #25 merged, adds DID Resolution

October 25, 2022 – Reviewing other work, I discovered the unannounced merge of #20 and commented asking to revert. https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/20#issuecomment-1291199826

December 14, 2022 – Brent Zundel created PR #27 to add DID Methods and DID Resolution to the deliverables section.

December 15, 2022 – DID WG Charter extended to “allow the group to prepare its new charter” Xueyuan xueyuan@w3.org https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-did-wg/2022Dec/0000.html

The Charter at the time of the December 15 extension https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/blob/b0f79f90ef7b8e089335caa301c01f3fc3f8f1ef/index.html

December 15, 2022 – Brent Zundel asserts consensus is not required. “There are no WG consensus requirements in establishing the text of the charter.” And “The time and place to have the conversation about whether the charter meets the needs of the W3C is during AC review.” https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/27#issuecomment-1353537492

January 19, 2023 — Christopher Allen raised issue #28 suggesting DID Resolution WG instead of DID WG. https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/issues/28

January 23, 2023 – Brent Zundel initially welcomes seeing a DID Resolution WG charter. https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/issues/28#issuecomment-1401211528

January 23, 2023 – Brent Zundel continues to argue that consensus does not apply: “This charter is not a DID WG deliverable. It is not on the standards track, nor is it a WG Note, nor is it a registry. Thus, the strong demands of WG consensus on its contents do not apply. Consensus comes into play somewhat as it is drafted, but primarily when it is presented to the AC for its consideration.” https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/27#issuecomment-1401199754

January 24, 2032 — Brent Zundel creates PR #29 offering an alternative to PR #27, excluding the offending language. https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/29

March 13, 2023 — Christopher Allen raises Pull Request #30 proposing a DID Resolution WG charter. https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/30#issue-1622126514

March 14, 2023 — Brent Zundel admits he never actually considered PR #30 “It was never my understanding that a DID Resolution WG would replace the DID WG. I do not support that course of action. If folks are interested in pursuing a DID Resolution WG Charter separate from the DID WG Charter, the place to do it is not here.” https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/30#pullrequestreview-1339576495

March 15, 2023 – Brent Zundel merged in PR #27 over significant dissent “The DID WG chairs have met. We have concluded that merging PR #27 will produce a charter that best represents the consensus of the DID Working Group participants over the past year.” “The inclusion of DID Methods in the next chartered DID WG was part of the W3C Director’s decision to overturn the Formal Objections raised against the publication of Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) v1.0. The chairs feel that that decision represents the consensus of the W3C and as such the inclusion of DID Methods as optional work in this charter is absolutely necessary.” https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/27#issuecomment-1470920464

March 21, 2023 – Announcement of intention to Appeal Joe Andrieu joe@legreq.com https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/pull/27#issuecomment-1478595775

March 23, 2023 – Clarification from Philippe Le Hegaret

‘The “should” is NOT a “must”, otherwise it would say so explicitly in the Director’s decision. In other words, the Working Group is allowed to disagree with the direction set by the Director.’ Personal email from Philippe

March 30, 2023 – DID WG Charter extended. “The goal of this extension is to allow the group to propose its new charter [2], which the chairs consider reasonably stable now. ” xueyuan xueyuan@w3.org https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-did-wg/2023Mar/0000.html

April 12, 2023 — Appeal of Chair Decision filed https://blog.joeandrieu.com/2023/04/12/fighting-for-consensus-at-the-w3c/

June 12, 2023 — A new process document is adopted. Removes Director. Rather than the “Director, the W3C Council, which is composed of TAG+AB+CEO, will now hear and resolve formal objections.” “Merge Chair Decision Appeal, Group Decision Appeal, and Formal Objection; clarify what can be objected to.” https://www.w3.org/2023/Process-20230612

May 9-10, 2023 – Advisory Committee meeting in Sophia Antipolis. Joe Andrieu attended. Neither co-chair attended.

May 11, 2023 — Joe Andrieu reports success on conversations with prior formal objectors ‘There was exceptional support for focusing on resolution rather than DID methods as the route to interoperability. “That would go a long way to addressing our concerns” and “Yep, that seems like the better way to do it” and “That seems reasonable, but I need to think on it a bit more [before I say it resolves the issues of our FO].” I think it’s fair to say that a focus on resolution (without any DID methods) would likely avoid a FO from 2 out of 3 and, quite possibly all 3. https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/issues/28#issuecomment-1543579206

May 11, 2023 — Brent Zundel claims confidence that we can “move through the charter development process and end up with something that no one objects to.“ https://github.com/w3c/did-wg-charter/issues/28#issuecomment-1544358479

May 22, 2023 – Pierre-Antoine Champin published survey to did-wg charter.

“Would you agree to sending the current version of the charter proposal to the Advisory Committee for review?”

This questionnaire was open from 2023-05-22 to 2023-06-20.

40 yes (85%)

6 no (15%)

https://www.w3.org/2002/09/wbs/117488/rechartering_survey/

July 26, 2023 — Philippe Le Hegaret dismisses appeal. “W3C team concurs there is no consensus” https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-did-wg/2023Jul/0000.html

August 8, 2023 – Proposed DID WG Charter Call for Review “There is not consensus among the current working group participants as to whether the charter should permit work on the specification of DID methods. This charter proposal includes the option for the group to do that work if there is sufficient interest. This follows the director’s advice in the DID Core 1.0 Recommendation decision [3] to include the specification of DID methods in the future scope of the work.” https://www.w3.org/2002/09/wbs/33280/did-wg-2023/

August 8, 2023 – Brent Zundel asserts in W3C Credentials Community Group meeting that “In my experience, Formal Objections are noted and are usually overridden…” https://w3c-ccg.github.io/meetings/2023-08-08/

No DID WG Meetings whatsoever after January of 2022.

These, I believe, are the relevant facts of the situation, covering the thread of this debate from its beginning through to today.

Why does it matter?

Because consensus is how the W3C delivers legitimate technical specifications.

Because the record clearly shows that the chairs never intended nor attempted to seek consensus and resolve objections to their initial proposal. In their defense, they argue consensus doesn’t apply, which if correct, would justify their behavior. However, we can’t see anything–neither in the member agreement nor in the process document–that constrain’s the requirement that chairs seek consensus to any particular activity.

We believe three points should prevail in this discussion:

First, we see the deference to the past director’s comments as completely outside the Process.

Second, regardless of intent or process, we believe that charter development for an existing working group MUST achieve consensus within that WG before advancing to AC Review.

Third, we see the chairs’ argument regarding the inapplicabilty of consensus to violate the fundamental point of the organization: consensuse-based collaboration.

Let’s look at each of these in terms of what it would take to deny these points.

For the first point, we could interpret the will of “The Director” in his response to the prior Formal Objections as a mandatory requirement.

As we asked formally in our appeal, it may well be that this outcome was always the intention of Staff. “Since the chairs are claiming a mandate from the Director as the justification for their decision, I am directly asking the Director if what is happening is, in fact, what the Director required.”

Staff answered this question by endorsing the Chairs’ decision, relying on the “Director’s comments” as justification. Staff and the chairs believe that it is appropriate for a past decision by the past Director to bind the future work of a Working Group.

I find this unreasonable and contrary to Process. Nowhere in any Process document does Staff or the Director get the right to mandate the work of working groups. Nor does the Process give Staff, Director or otherwise, the right to bind future work of WGs.

Even Phillippe Le Hegaret acknowledged that the Director’s comments did not require the group adopt that recommendation: “It’s a SHOULD not a MUST.” And yet, he claims that his decision to advance the current Charter “follows the director’s advice in the DID Core 1.0 Recommendation decision”.

Working Groups should be the sole determinant of the work that they perform. It is not Staff’s role to direct the technical work of the organization. It’s Staff’s role to support the technical work of the organization, by ensuring the smooth operation of Process.

We do not buy the argument that Ralph Swick, acting on behalf of the past Director in a decision made about a previous work item, appropriately justifies the willful denial of consensus represented by this charter.

The fact of the matter is that DID interoperability is a subtle challenge, not well understood by everyone evaluating the specifications. If we could have had a conversation with the Director–which I asked for multiple times–perhaps we could have cleared up the confusion and advanced a proposal that better resolves the objections of everyone who expressed concerns. But not only did that conversation not happen, it CANNOT happen because of the change in Process. We no longer have a Director. To bind the future work of the DID WG to misunderstandings of Ralph Swick, acting as the Director, is to force technical development to adhere to an untenable, unchallengeable mandate.

What we should have had is a healthy conversation with all of the stakeholders involved, including the six members of the WG who opposed the current charter as well as anyone other participants who cared to chime in. The chairs explicitly prevented this from happening by cancelling all working group meetings, failing to bring the matter to the groups attention through the mailing list, or otherwise attempting to arrange a discussion that could find a proposal with weaker objections as required by process.

Failing that, we should have had a W3C Council to review my appeal as per Section 5.5 and 5.6 of the current Process. That council may well have been able to find a proposal that addressed everyone’s concerns. That also did not happen. Rather than respond to my objection in a timely manner, staff advanced the non-consensual charter to AC review.

Finally, even if we accept that Ralph Swick, acting as the Director, in fact, officially represented the consensus of the W3C in the matter of the DID Core 1.0 specification (for the record, we do), the recommendation that resulted represents the formal W3C consensus at the time of the DID Core 1.0 specification, solely on the matter of its adoption as a Recommendation. It cannot represent the consensus of the W3C on the forced inclusion of unnamed DID Methods in the next DID WG Charter, because the organization has not engaged in seeking consensus on this matter yet. Not only did the chairs ignore their responsibility to seek consensus, Staff has as well.

I would like to think that every WG at the W3C would like to be able to set their own course based on the consensus of their own participants, rather than have it mandated by leadership.

For the second point, you could endorse that charter development is not subject to consensus, as argued by the Chairs.

The chairs claim that “This charter is not a DID WG deliverable. […] Thus, the strong demands of WG consensus on its contents do not apply.”

I find this untenable on two different grounds.

First, the Process does not restrict the commitment to consensus to just Working Group deliverables. The language is broad and unambiguous: “To promote consensus, the W3C process requires Chairs to ensure that groups consider all legitimate views and objections, and endeavor to resolve them, whether these views and objections are expressed by the active participants of the group or by others (e.g., another W3C group, a group in another organization, or the general public).”

The Process in fact, includes examples of seeking consensus that have nothing to do with formal deliverables.

Second, this interpretation would mean that, according to process, ANYONE could propose a new Working Group charter, with the same name and infrastructure as a current Working Group, WITHOUT seeking the consensus of the Working Group involved. All one needs is for Staff to support that effort. On their own initiative, Staff can simply hijack the work of a working group by recruiting chairs willing to propose a new charter without the input of the current group.

This is untenable. If a Working Group is still in existence, it should be a fundamental requirement that any charter proposals that continue that work achieve the consensus of the working group. Of course, if the WG is no longer operating, that’s a different situation. But in this case, the WG is still active. We even discussed the Charter in our meeting at TPAC where upon its first presentation no fewer than five participants objected to including DID Methods in scope.

Frankly, if a Charter proposal does not represent consensus of the group selected by staff to develop the charter… it should not advance to AC Review. Full stop.

That’s the whole point of charter development: for a small group of motivated individuals to figure out what they want to do together and propose that to the organization. If that small group can’t reach consensus, then they haven’t figured it out enough to advance it to AC Review. They should go back to the drawing board and revise the proposal until it achieves consensus. THEN, and only then, should it be proposed to Staff for consideration. When Staff receives a charter proposal that lacks consensus, it should reject it as a matter of course, having not met the fundamental requirements.

For the third point, you could accept the position that the chairs met their duty to seek consensus simply by asserting that there is no consensus.

This argument was raised by other W3C members (not the chairs or staff): the W3C has historically given broad remit to chairs to determine consensus, so whatever they do for “consensus” is, by definition, canon. This disposition is noted in the process itself “Chairs have substantial flexibility in how they obtain and assess consensus among their groups.” and “If questions or disagreements arise, the final determination of consensus remains with the chair.”

As the current discussion has shown, that latter statement is, as a matter of fact, incorrect. The chairs asserted a determination of consensus in this matter “PR #27 will produce a charter that best represents the consensus of the DID Working Group participants over the past year” which Staff judged inadequate: “There is not consensus among the current working group participants as to whether the charter should permit work on the specification of DID methods.” So, either the policy is in error because, in fact, the Staff is the ultimate determiner of consensus, or, Staff ignored process to impose their own determination.

However, even if Chairs have wide remit to determine consensus, the process unequivocally requires chairs to do two things:

- ensure that groups consider all legitimate views and objections

- endeavor to resolve [those objections]

In short, the chairs must actively engage with objectors to resolve their concerns.

The chairs did not do this.

First, they did not do any of the following suggestions in the process document about how to seek consensus:

- Groups should favor proposals that create the weakest objections. This is preferred over proposals that are supported by a large majority but that cause strong objections from a few people. (5.2.2. Managing Dissent https://www.w3.org/2023/Process-20230612/#managing-dissent)

- A group should only conduct a vote to resolve a substantive issue after the Chair has determined that all available means of reaching consensus through technical discussion and compromise have failed, and that a vote is necessary to break a deadlock. (5.2.3 Deciding by Vote) https://www.w3.org/2023/Process-20230612/#Votes

- A group has formally addressed an issue when it has sent a public, substantive response to the reviewer who raised the issue. A substantive response is expected to include rationale for decisions (e.g., a technical explanation, a pointer to charter scope, or a pointer to a requirements document). The adequacy of a response is measured against what a W3C reviewer would generally consider to be technically sound. (5.3 Formally Addressing an Issue https://www.w3.org/2023/Process-20230612/#formal-address )

- The group should reply to a reviewer’s initial comments in a timely manner. (5.3 Formally Addressing an Issue https://www.w3.org/2023/Process-20230612/#formal-address )

The record shows that chairs, rather than doing any of the above recommended actions for consensus, consistently avoided seeking consensus by dismissing concerns and merging PRs without actually seeking to address objectors’ concerns.

PR #20 still has no comments from either Chair. It was merged in over objections despite the working groups exceptionally consistent practice that unless there is consensus for a given change, PRs don’t get merged in.

In fact, controversial edits in this working group regularly receive a 7-day hold with, at minimum, a Github label of a pending action (to close or merge), and often an explicit mention in minutes of the meeting in which the change was discussed. PR #20 was merged by executive fiat, without adherence to the norms of the group and the requirements of process. If you feel charters don’t need consensus, maybe you’re ok with that. We’re not.

It’s clear that in the case of PR #20, Brent Zundel made an executive decision that was contrary to the groups established norms of requiring consensus before merging. Given that Brent never wavered in his commitment to the specific point of including DID Methods in scope as the “only option”, it’s clear that, at least on that point, he never intended to seek consensus.

In PR #27 Brent Zundel and Pierra-Antoine Champin (team contact) dismissed the concerns of objectors rather than “endeavoring to address” them.

Brent asserts that “flexibility in the charter does not require a group to perform any work” And “a future charter that doesn’t include possible DID Methods will be rejected” and “the strong demands of WG consensus on its contents do not apply.”

Pierre-Antoine asserts that “Considering the two points above, the chairs’ decision is in fact quite balanced.” and “But I consider (and I believe that others in the group do as well) that plainly ignoring this recommendation from the director amounts to painting a target on our back.”

Not once did Brent, Dan, or Pierre-Antoine acknowledge the merit of the concerns and attempt to find other means to address them.

PR #29 Remove mention of DID Methods from the charter was ostensibly created to seek input from the WG on the simplest alternative to #27. Unfortunately, not only did the chairs fail to make any comments on that PR, there remain four (4) outstanding change requests from TallTed, kdenhartog, Sakurann, and myself. This PR was never more than a distraction to appear magnanimous without any actual intention to discover a better proposal. If the chairs had been actually exploring PR #29 as a legitimate alternative to PR #27, they would have engaged in the conversation at a minimum, and at best, actually incorporated the suggested changes so the group could reasonably compare and discuss the merits of each approach.

PR #30 Charter for the DID Resolution WG was created in response to a request from TallTed, and initially supported by Brent Zundel, only to see him reverse course when he understood it was an alternative proposal to the DID WG Charter: “I do not support that course of action. … the place to [propose an alternative] is not here.”

Not once, at any time, did Brent, Pierre-Antoine, or Dan Burnett acknowledge the merit of our concerns. They did not ask objectors how else their concerns might be addressed. Not once did they attempt to address my (and others’) concerns about DID method over-centralization caused by putting DID Methods in scope.

Instead, they simply refused to engage objectors regarding their legitimate matters of concern. There were no new proposals from the chairs. There were no inquiries about the “real motivation” behind our objections in an effort to understand the technical arguments. There weren’t even rebuttals from leadership to the technical arguments made in opposition to DID Methods being in scope. It was clear from ALL of their correspondence that they simply expected that the rest of the WG would defer to their judgment because of the prior Director’s comments.

It is our opinion that in all their actions as chairs, WG Chairs MUST seek consensus, whether it is a WG deliverable, a charter, or any W3C matter. That’s the point of the W3C. If chairs can ignore process, what good is process? If staff can ignore the process, how are we to trust the integrity of the organization?

Finally, on the matter of the chairs and process, I find Brent Zundel’s assertion in the August presentation to the Credentials Community Group particularly problematic: “In my experience, Formal Objections are noted and are usually overridden”.

In other words, Brent believes that the Process, which describes in great detail what is to happen in response to a Formal Objection, doesn’t usually apply.

The fact is, he may end up being right. Given the improper dismissal of my appeal, the Process, in fact, does not appear to matter when it comes to the DID WG charter.

TECHNICAL FUNDAMENTALS

The primary technical objection to putting DID Methods in scope is simple conflict of interest. By empowering the DID WG to develop specific DID Methods, it would result in the group picking winners and losers among the 180+ DID Methods currently known. Not only would that give those methods an unfair advantage in the marketplace, it would affect WG deliberations in two important ways. First, the working group would, by necessity, need to learn those selected methods, placing a massive burden on participants, and elevating the techniques of that particular method to accepted canon–which will inevitably taint the DID Core specification with details based on those techniques. Second, this will require the group to evaluate, debate, and select one or a few of those 180+ methods, which will suck up the available time and energy of the working group, forcing them to work on “other people’s methods” rather than advancing the collective work that all DID Methods depend on. Those who want to pursue DID Methods at theW3C should propose their own charter based on a specific DID method.

Our second technical objection is more prosaic: there are no DID Methods ready for W3C standardization, as evidenced by the blank check in the current charter request. It may be within the bounds of the W3C process to authorize such an open ended deliverable, but we believe it is a fundamental problem that the chairs cannot even recommend a specific method for inclusion in the charter. Frankly, this weird hack of not specifying the method and restricting that work to First Public Working Draft (FPWD) status lacks integrity. If it is important for the group to develop a method, name it and make it fully standards track, without restriction. This middle-way is a false compromise that will satisfy no one.

INTEROPERABILITY GOALS

A significant failing of the initial DID Core specification was a failure to develop interoperability between DID Methods. This lack of interoperability was cited as a reason for multiple Formal Objections to that specification. We concur, it’s problem.

However, the problem was not a result of too many DID Methods, nor would it be resolved by forcing the standardization of one or more exemplars. It was a problem of scope. DID core was not allowed to pursue protocols and resolution was intentionally restricted to a mere “contract” rather than a full specification.

The result of those restrictions meant the WG could NOT achieve the kind of interoperability we are all seeking.

We believe the answer is simple: standardize DID Resolution. Not restricted to FPWD status, but actually create a normative global standard for DID Resolution as a W3C Recommendation.

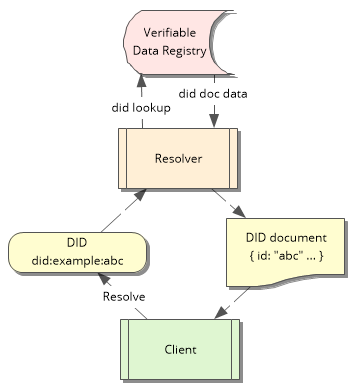

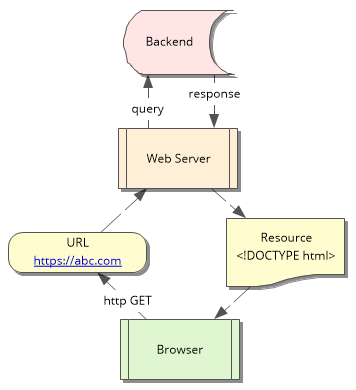

By defining a common API that all DID Methods can implement to provide an interface for a back-end verifiable data registry, we allow any system that can support those implementations an equal opportunity to interoperate with any other, just like HTTP allows any browser to reach any website, regardless of the back-end technology that does the heavy lifting.

That’s how we get to interoperability.

Distracting the group with DID Method specifications would just limit the time and resources the DID WG can bring to bear on solving the real issue of interoperability between methods.

More technical and interoperability details are discussed in our appeal.

RESPONDING TO CRITISMS

Finally, for those still reading, I’d like to address some criticisms that have been raised about my approach to this problem.

First, the assertion that this debate is going to end up in AC Review, so we should have it there and not in the WG.

The debate was not predestined to go to AC review. Like all objections under Process 2023, it should have been resolved in a council. Staff inappropriately accelerated the charter to AC Review despite an ongoing objection and requests by the objector to delay advancement until the matter could be resolved.

Second, the AC is not the appropriate place for a working group to work out its internal disagreements. The AC is the place where other member organizations have a chance to review and comment on proposed work done by the organization as a whole. This is a fundamental principle that, in other contexts, is known as federalism. It isn’t the job of the AC to tell every WG what to do. It’s the job of the AC to vet and confirm the work actually done by the WG. For staff and chairs to deny due process to my objection is, in fact, denying the ability for the AC to review the best proposal from the Working Group and instead requiring the AC to have a meaningless debate that will absolutely result in a council.

To reflect Philippe’s argument back, since the underlying objection is going to be decided in a council anyway, why didn’t we start there? Especially since that is what process requires.

Third, Philippe quoted the following Process section in his discussion of my appeal, despite ignoring the first part of the sentence.

“When the Chair believes that the Group has duly considered the legitimate concerns of dissenters as far as is possible and reasonable, the group SHOULD move on.” [emphasis mine]

The group did NOT duly consider the legitimate concerns of objectors. Instead, the chairs intentionally avoiding any substantive discussion on the topic. There is no evidence at all that the chairs ever considered the legitimate concerns of objectors. They dismissed them, ignored them, and argued that the WG’s github is not the place to have this debate, the AC is.

So, because Staff and the chairs believed it was ultimately going to AC Review, they collectively decided to ignore their obligations: of Chairs to seek consensus within the WG and of Staff to seek consensus through a W3C Council after my appeal.

Finally, I’ll note that my disagreement has been described by one of the chairs as “Vociferous”, “Haranging”, and “Attacking”. I find this characterization to be inappropriate and itself a CEPC failure. “When conflicts arise, we are expected to resolve them maintaining that courtesy, respect, and dignity, even when emotions are heightened.”

The civil exercise of one’s right to challenge authority is fundamental to a free society and vital to any collaborative institution. To be attacked because I chose to engage in conversations that the chairs were trying to avoid, is inappropriate. To be attacked because I filed an appeal, as clearly allowed in the Process, is inappropriate. To attack those who disagree with you is neither collaborative, nor is it an effective mechanism to seek consensus.

SUMMARY

This charter never should have made it to the AC. It unfairly hijacks the DID WG name and its work, without the consent of the current DID WG. Worse, it does so in a way that fundamentally undermines the decentralized nature of Decentralized Identifiers.

This charter should be rejected and returned to the DID WG to find a proposal with weaker objections, one that represents the collective will of the working group and legitimately continues the work in which we all have invested our professional careers.